In recent years, approximately 10% of households in the United States reported experiencing food insecurity. This represents over 32 million Americans who can’t afford balanced meals, are worried food will run out or are going hungry throughout the day.

America is one of the wealthiest nations in the world. So why are so many Americans facing food insecurity? Of those who have access to food, how many households have access to healthy, nutritious food?

Understanding the link between food insecurity and health outcomes is crucial in addressing this pervasive issue.

Lack of Access: Food Apartheid & High Costs

A food desert is a geographic area where residents must travel further to reach a supermarket with fresh food options. Recent USDA data indicates that 54 million Americans struggle with food insecurity in America, and about 23 million Americans live in a food desert. Additionally, 2 million of those residing in food deserts lack access to a car, creating an additional barrier to obtaining healthy food.

Recognizing the inequities in food access can guide us in effectively creating more equitable food systems and addressing food insecurity more broadly.

Together, these 3 major factors impact individual choices on food:

- Cost: Healthier foods (like fruits and vegetables) are generally more expensive

- Location: Stores are hard to reach without reliable transportation

- Time: Home-cooked meals take time and equipment to prepare

Cost

Income and race are major predictors of food insecurity. Compounding these are employment and disability status—unemployment makes it harder to meet basic food needs, and adults with disabilities are at a higher risk of food insecurity due to limited employment opportunities.

Food deserts exist mostly in communities of color, with White neighborhoods averaging 4 times as many supermarkets than their predominantly Black counterparts. In 2020, 29% of low-income families were food insecure, and Black households were over two times more likely to be food insecure than the national average. Moreover, approximately 1 in every 4 indigenous Americans face food insecurity. To overcome this food apartheid, we must acknowledge how colonialism have shaped food spaces and the intersectional inequalities that create inequitable food systems.

Location

While economic injustices are the main drivers of food insecurity, location also plays a critical role. Research has shown that historically discriminatory policies, such as redlining of African American communities and land theft from Native nations, have mapped to current food insecurity patterns—and suggest that racism, housing discrimination, forced displacement, and other systemic factors compound individual level risks of food insecurity for historically marginalized populations.

Rural communities must travel far distances, and urban communities are often food swamps, where people are forced to turn to convenience stores, fast food, and junk food. In these small neighborhood stores, it may still be difficult for minorities to find culturally appropriate food, choices are limited and may not meet dietary restrictions, and there is an upcharge on products, especially fresh produce.

Time

Those who can overcome costs and distance must combat the next barrier—cooking a meal. Studies show that home-cooked meals contain more fiber and less sodium and sugar. However, meal preparation takes time, and the amount of time a family can devote to cooking depends on work schedule, work commute time, family composition, and other factors. It also depends on the availability of other resources such as electricity, kitchen appliances, and kitchen supplies, which poses an additional barrier for unhoused populations.

When facing these barriers, individuals and families with strained budgets are likelier to turn to processed and fast foods. This is cheaper in the short-term—saving time and money—but the long-term consequences are deadly.

The Health Outcomes

These nutrient-deficient diets increase the risk of chronic illnesses such as hypertension, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. They are an underlying cause of the major racial disparities in chronic illnesses. In fact, minorities are up to two times more likely to have these chronic illnesses. Further exacerbating this issue, food-insecure children also face a higher risk of developmental issues compared to food-secure children.

While the health care system can help manage these diseases, addressing a root cause—lack of access to healthy food due to cost and other barriers—can help lower the prevalence of chronic illnesses and consequently decrease mortality rates.

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programs: CalFresh

Food assistance programs aim to address barriers and increase access to food, thereby mitigating food insecurity and improving food insecurity and health outcomes. Programs like the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) are key governmental public health efforts designed to bolster food security.

In California, the CalFresh program, a state-specific SNAP initiative, helps families access healthy food by providing an electronic benefit transfer (EBT) card usable at most grocery stores and farmers’ markets. CalFresh targets residents with low-to-no income, limited property, or those who receive state supplements. Reflecting California’s diverse demographic, a significant portion of the program’s beneficiaries includes naturalized citizens (19%), refugees (15%), and other noncitizens (15%), highlighting its role in supporting varied communities in overcoming food insecurity.

Demystifying Enrollment: A Path to Food Security

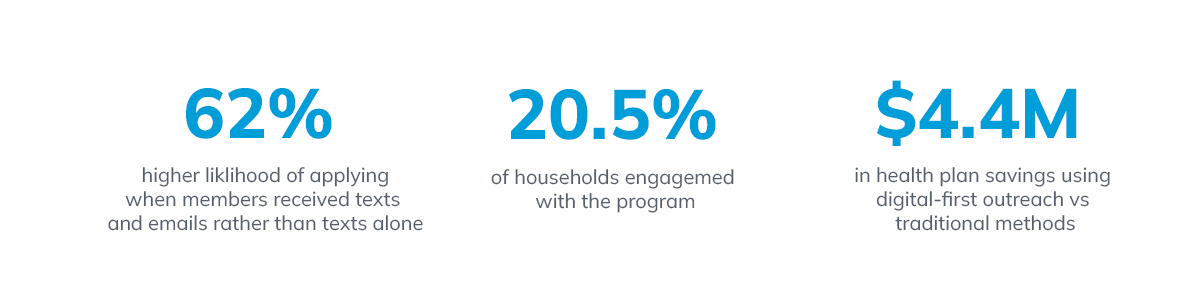

To increase the number of eligible people who sign up for CalFresh, mPulse sent tailored digital health communications to over 2.2 million eligible households using both short message service (SMS) and email modalities. The content was curated to feel empathic, relatable, and straightforward, ultimately increasing awareness and education around the CalFresh program and destigmatizing negative perceptions.

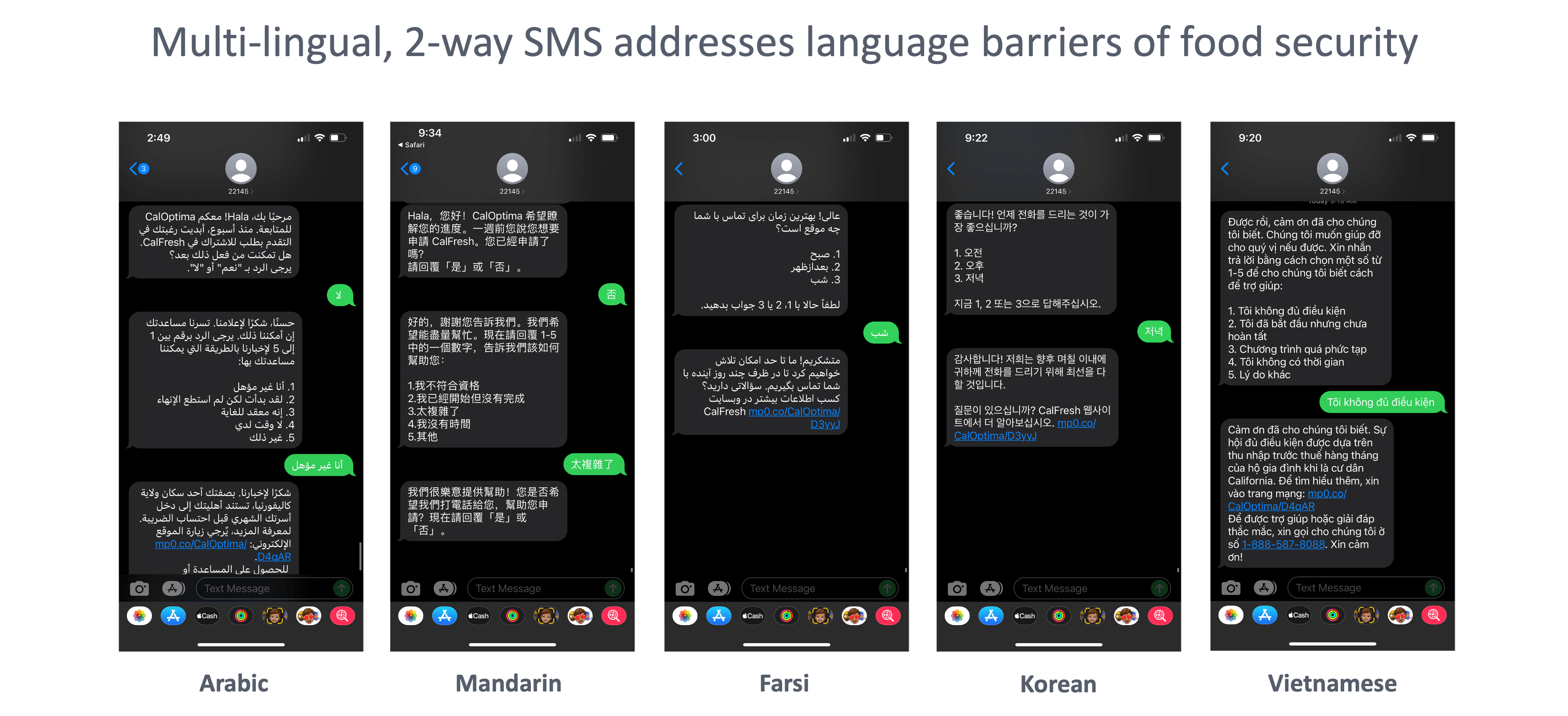

It defined the application process, gave ideas on how much money a member was eligible for, and made it easy to start the application process. Multimedia messaging service (MMS) infographics were included to make the information easier to understand. This messaging, available in 7 languages, aimed to drive action by increasing conversations around understanding of eligibility, recertification, and the application process.

Outcomes showed that messaging was successful overall in increasing literacy around enrollment and empowering members to enroll, with 20.5% of households engaging with the content. More specifically, 62,000 households initiated digital applications, and 22,000 households completed enrollment in supplemental food benefits. This translates to an estimated cost savings of $4.4 million for using digital-first outreach compared to traditional outreach methods.

With tailored health communications, benefits programs like CalFresh can reach more households, bridge the gap in food insecurity, and ultimately reduce health disparities. These efforts are crucial in devising effective food insecurity solutions.

Read our white paper, Digital Engagement Strategies to Support Health Equity, to learn more about using digital engagement strategies to promote health equity and tackle food insecurity challenges.